Dr. Martens champions sustainable fashion

Genix Nappa, a new material made of leather offcuts, aims to reduce waste

In 1997 a Californian surfer named Charles Moore was heading home from a sailing race in Hawaii. Exhausted from the event, Moore decided to take a short cut across the edge of the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. Seafarers had long avoided that region; it’s a perennial high-pressure zone that sits under a massive, slow-moving vortex of warm equatorial air that acts like a magnet to surrounding winds.

Upon entering the area, Moore noticed more and more flotsam surrounding his 50-foot catamaran, until eventually he was brought to a standstill. Looking down from the stern he could barely believe his eyes: his boat was no longer surrounded by the blue of the ocean, but by a dense field of bottle caps, toothbrushes, Styrofoam cups, detergent bottles, pieces of polystyrene and plastic bags, as far as he could see.

Moore had just discovered a ‘land mass’ allegedly more than fifty times the size of Great Britain: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The undulating monstrosity is reported to be 15 million square kilometres in size and contains 46,000 pieces of plastic per square kilometre. It is responsible for the deaths of a million sea birds and over 100,000 marine mammals a year.

And every day it gets a little bigger.

And it is not degrading. Not even slowly.

It’s not a dystopian scare-story about the future - this thing really exists. And 80-90% of its volume comes from waste initially discarded on land.

Overwhelming, isn’t it.

It brings a simple fact of life into sharp relief: stuff that we throw away that doesn’t degrade has to go somewhere. When the bin men take it away they’re only taking it out of sight: it still exists. No microbe has yet evolved that can feed on plastic, so whether it exists in our kitchen bin or elsewhere, it won’t stop existing.

The only sustainable management method is to control the amount we throw away, and re-use and recycle what we can.

The trouble is, as compelling as the argument is, young people have stopped listening to it. Research shows that they understand the need to recycle, loosely speaking they understand the consequences of not recycling, but recycling just doesn’t occur to them at the moment of action.

They’re not entirely to blame for that detachment; in this ruthlessly competitive multimedia age their attention is precious and they haven’t yet been made to feel like recycling is worth paying mind to.

So for young people, the topic ends up just floating somewhere out there in the distance. Just like The Pacific Garbage Patch.

They don’t really need persuading to recycle; they need the occasional reminder that it’s just as much their job as anybody else’s.

Reminders, not nagging: it’s a fine line and (as anyone who shares a living space with teenagers might know) the difference can be as simple as finding the right tone of voice.

That’s how young adults today want to be schooled: they don’t want to be told off or frightened or patronised, they just want to be pointed in the direction of the right thing to do.

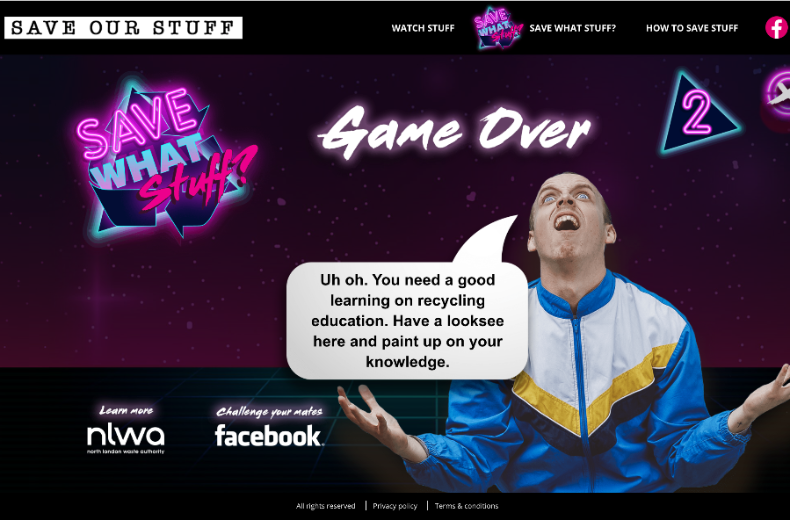

In 2017, North London Waste Authority decided that enough was enough. They wanted to address the issue of young people ignoring their recycling responsibilities.

They wanted to supplement their regular, instructional activities with something high-level, focused on bringing the topic to the surface of consciousness for young people in North London.

So we took it back to basics, stripping away everything but the essential message:

It’s not a good idea to throw away useful stuff.

Young people love their stuff. Stuff like trainers and mobile phones and makeup brushes. Perhaps they don’t always like to admit it, but their stuff helps them to get along in the world and be who they like to be.

The Save Our Stuff campaign introduced North London millennials to a protagonist named Arjen, who projected them cautionary messages from an imagined future. Arjen’s tales aren’t tragic or catastrophic. They’re not even particularly redemptive. They just invite young people to stop and think about recycling through a simple, digestible series of offbeat stories.

The first film, which went live in January 2017, focused on the everyday human value of plastic and the second, to go live this month, will focus on glass.

AND IT’S STARTING TO CHANGE BEHAVIOUR

It’ll be a while before we see the fruits of our labour in terms of recycling tonnage. But interim campaign research analysis carried out by Neilsen showed that the idea is working: 20% of 18-34s who had seen the ad three or more times, said it had inspired them to think about recycling more in the future. This means they were almost twice as likely to act as those who had not seen the campaign.

Agency: SAVE OUR STUFF, Therapy

Specialist in creating world class ideas for brands who want to change something. I work for Therapy, an award-winning creative shop on Clerkenwell Green.

Looks like you need to create a Creativebrief account to perform this action.

Create account Sign inLooks like you need to create a Creativebrief account to perform this action.

Create account Sign in